By David Dodge and Duncan Kinney

Lawrence Grassi was a trailblazer. An immigrant from Italy he was a respected mountaineer and guide who built and maintained many of the original trails throughout the mountains around Canmore, Alberta.

Short of stature and eschewing alpine guide stereotypes for suspenders and hobnail boots Grassi was one of the key personalities in Canmore’s early history. And the school that bears his name, Lawrence Grassi middle school, has blazed a trail much in its namesake’s fashion. Nothing too fancy, but a lot of hard work and common sense can go a long way.

Lawrence Grassi middle school is 70 per cent more efficient than a comparable building. The difference in utility bills between it and the 1920s era school it replaced is $120,000 a year. And oh yeah, they did it all on budget.

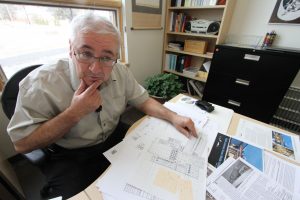

Ken Riordan is a modern day Lawrence Grassi blazing a trail to energy efficiency on a budget at Lawrence Grassi middle school in Canmore, Alberta. Photo David Dodge

Home to 391 students between the grades of five and eight (and expanding to Grade 4 next year) Grassi is your typical Canadian mid-size school. There is a wood shop, a teacher’s lounge, portables and the building was commissioned in 2008.

Ken Riordan is the facilities manager for this and five other schools in the Canadian Rockies School Division. His school division also built Banff Community High School, the very first LEED certified school in Canada. He knows how to build an efficient building on a budget.

So how did they do it?

“The systems we put in here are meat and potatoes, it wasn’t a Cadillac,” says Riordan.

The walls are R-24 and the ceiling is insulated to R-40. The triple paned windows let in plenty of light but the killer app is the concrete slab floor.

The thermally massive slab floor allows for both passive heating and cooling and evens out the temperature swings over the course of the day. There are also pipes that go through the slab for both heating and cooling and once the slab is charged up it retains either the heat or cold a long period of time.

The building also has high-efficiency condensing gas boilers and there is a rooftop heat recovery ventilator that preheats the fresh cold incoming air with the stale warm air on its way out.

And it wasn’t just in the construction process and systems where they found efficiencies, they found them after the building was operational as well. They discovered they were over lit. “We went from having 204 bulbs down to 113 bulbs, reducing our wattage use considerably,” says Riordan.

Every dollar saved is an extra dollar that the school board can invest in teachers, programs and students.

“It’s unreal. You don’t realize how much you spend day to day on the bills over a year but when you starting thinking about two, three, four years the amount of money that’s generated over such a long period of time you’re looking at half a million dollars,” says principal Brian Wityshyn.

“That money that’s saved that can actually go back into the classrooms.”

On Budget

You don’t hear it often said about public infrastructure projects, but this school district was right on budget.

“The budget for the school was $11.2 million… and we came in at $11.2 million,” says Riordan.

Brian Wityshyn, principal of Lawrence Grassi middle school in the common space of his energy efficient school. The school was designed to achieve LEED silver status on a budget but the district now thinks it will achieve LEED gold status. Photo David Dodge

One of the ways they did it was by sourcing materials from as close by as possible.

“At the time we built this building steel was very expensive, it was through the roof. And wood was a cheaper alternative so we went with wood throughout the building to help bring our costs down,” says Riordan.

Not only are the exposed wood beams and pillars gorgeous architectural features, but they came from just over the border in British Columbia. The cement came from a plant ten minutes away.

The building looks like it will end up with LEED Gold status and one of the things that process prioritizes is minimizing waste, both in any demolition and during construction.

They ended up diverting 86 per cent of all materials, both construction and demolition, from going to the landfill. And by partnering with a local church group the school district was able to ship four container loads, things like door knobs, door handles, wiring, breaker panels, desks, chairs, blackboards and tack boards down to help build schools Guatemala.

Trailblazing

It’s this accumulation of common sense that makes Lawrence Grassi school such an example for what regular buildings, builders and project managers can accomplish.

“The world needs Grassis… We need trail makers, men and women who will seek new paths, make the rough places smooth, bridge the chasms that now prevent human progress, point the way to high levels and loftier achievements.”

That’s a quote from Member of Parliament J.S. Woodsworth from 1938 about Lawrence Grassi. I couldn’t agree more, the world does need more Grassi’s (guides or schools). Using far less energy isn’t some kind of utopian dream, regular work-a-day folks are now bridging those chasms and it’s getting easier and easier to follow in trail they’re breaking.

[flickrshow:72157633382488450,width=625]